Join the Essig Museum and the Pacific Coast Entomological Society

for a special screening of “The Love Bugs“

8:00pm on 5 September 2019, at 2040 Valley Life Science Building

Over the course of 60 years, Lois and Charlie O’Brien, two of the foremost entomologists and pioneers in their field, traveled to more than 67 countries and quietly amassed the world’s largest private collection of insects. He was the Indiana Jones of entomology and she was his Marion Ravenwood. Their collection is a scientific game-changer with more than one million specimens and more than 1,000 undiscovered species. During the past several years, however, Charlie and Lois have grappled with the increasingly debilitating effects of Charlie’s Parkinson’s disease and the emotional toll it takes on Lois. They realize that a chapter of exploration and discovery is coming to an end in their lives. But they live in a time when the beleaguered field of science needs them most, and the O’Briens know they need to keep fighting for it. So they turn to their 1.25 million insects for a little help! The Love Bugs interweaves the O’Briens’ present day journey with animated watercolor illustrations that reveal their past in a humorous and poignant documentary short that explores the nature of Love–and the love of Nature–and what it means to devote oneself completely to both.

Charlie and Lois garnered worldwide attention in 2017 when they announced that they would be donating their $10 million dollar insect collection to Arizona State University. Their collection will reshape entomology for years to come, but outside of entomology circles it was not widely known that such a valuable collection existed. We live in a time when insect populations are declining worldwide at an alarming rate. This decline has a domino effect that could impact all other aspects of an ecosystem and humanity as a whole and the O’Briens’ collection is not only a snapshot of the past of insect life on this planet. It is also a valuable key to providing insights into the potential future of insect life and biodiversity patterns. We want this film to inspire wonder and reverence for the complexity and beauty of insects. We also live in a time when the value of teaching science and the value of investing in science is being questioned at a federal level. We deeply need stories that can help foster a paradigm shift by showcasing scientists as human beings–not only as people who passionately dedicate their lives to something that others might see as trivial, but as human beings whose work is crucial and with whom we can empathize.

Sadly, Charlie O’Brien died on August 10, 2019.

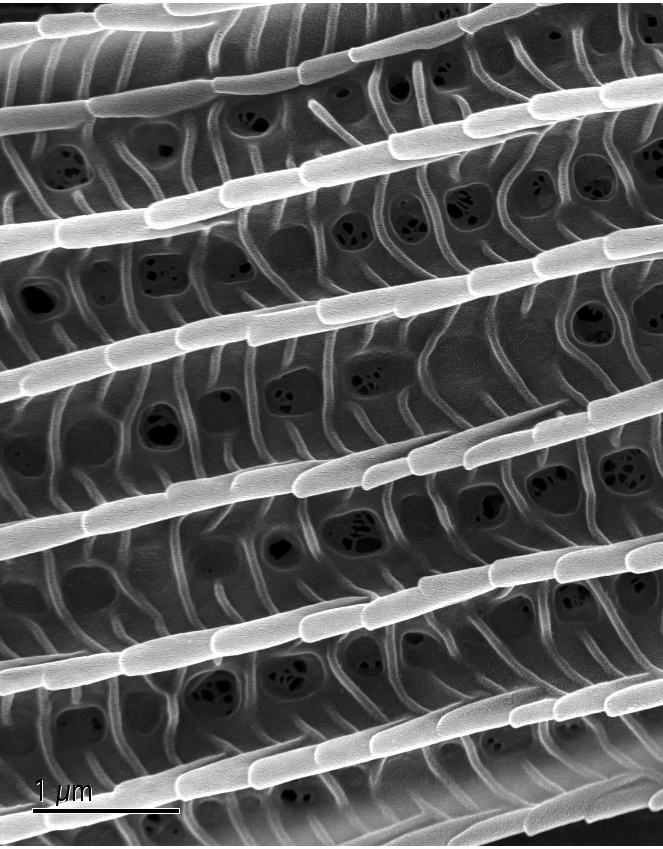

Have you ever touched the wings of a moth or butterfly and gotten some “powder” on your fingers? That powder is actually tiny scales, like on a fish or lizard, or like the feathers of a bird. These scales give butterflies and moths their scientific name Lepidoptera (from the Greek Lepido = scale, and ptera = wing). Each scale can be a different color and when placed next to each other, the mosaic makes up the color patterns we see. Some are brightly colored to warn that this species does not taste good (aposematism), or look like distasteful species (Batesian mimicry), while others look like eye spots to startle predators (image to the left), and still others form a camouflage pattern to blend in with their background.

Have you ever touched the wings of a moth or butterfly and gotten some “powder” on your fingers? That powder is actually tiny scales, like on a fish or lizard, or like the feathers of a bird. These scales give butterflies and moths their scientific name Lepidoptera (from the Greek Lepido = scale, and ptera = wing). Each scale can be a different color and when placed next to each other, the mosaic makes up the color patterns we see. Some are brightly colored to warn that this species does not taste good (aposematism), or look like distasteful species (Batesian mimicry), while others look like eye spots to startle predators (image to the left), and still others form a camouflage pattern to blend in with their background. Most colors are caused by pigments that form inside the individual scales and reflect light through holes on the scale surface (image to the right), while others, especially blues, are structural and result from light refracting off of ridged surfaces, like looking at the underside of a DVD. For more information on how blue (structural) colors are formed on butterflies watch KQED’s Deep Look episode “

Most colors are caused by pigments that form inside the individual scales and reflect light through holes on the scale surface (image to the right), while others, especially blues, are structural and result from light refracting off of ridged surfaces, like looking at the underside of a DVD. For more information on how blue (structural) colors are formed on butterflies watch KQED’s Deep Look episode “

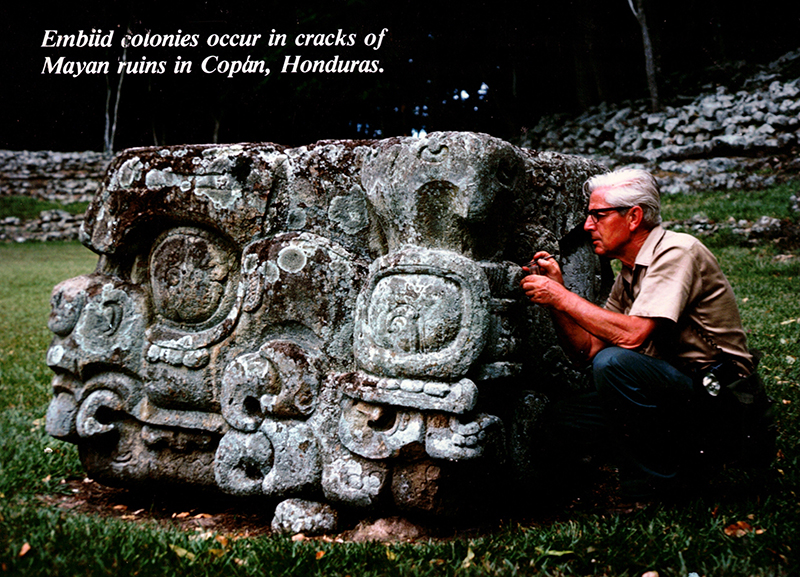

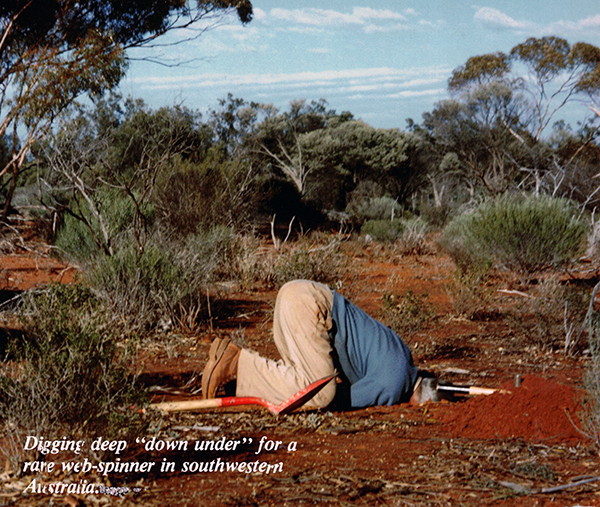

Edward S. Ross (1915-2016) was a pioneer of close up photography. Ed received his PhD in 1941 with the Department of Entomology at UC Berkeley, where he was a teaching assistant for E.O. Essig. Before finishing his degree he was offered the position of Curator of Entomology at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco in 1939, and two years later became chair of the entomology department, a position he held for 41 years. Initially Ed was interested in Histerid beetles, but soon switched to webspinners (Embiidina), a group for which little was known at the time. His studies took him around the world, particularly to the tropics where webspinners are most diverse. During his travels Ed photographed arthropods, plants, mammals, people, and natural landscapes. His images appeared in numerous publications including National Geographic Magazine, Insects Close Up, and Insects and Plants. In 2018, Ed’s collection of ~100,000 35mm slides were generously donated to the Essig Museum of Entomology by his wife, Sandra Miller Ross, to be digitized and made available for research, education, and outreach. Once digitized, the images will be available through

Edward S. Ross (1915-2016) was a pioneer of close up photography. Ed received his PhD in 1941 with the Department of Entomology at UC Berkeley, where he was a teaching assistant for E.O. Essig. Before finishing his degree he was offered the position of Curator of Entomology at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco in 1939, and two years later became chair of the entomology department, a position he held for 41 years. Initially Ed was interested in Histerid beetles, but soon switched to webspinners (Embiidina), a group for which little was known at the time. His studies took him around the world, particularly to the tropics where webspinners are most diverse. During his travels Ed photographed arthropods, plants, mammals, people, and natural landscapes. His images appeared in numerous publications including National Geographic Magazine, Insects Close Up, and Insects and Plants. In 2018, Ed’s collection of ~100,000 35mm slides were generously donated to the Essig Museum of Entomology by his wife, Sandra Miller Ross, to be digitized and made available for research, education, and outreach. Once digitized, the images will be available through

Ride, walk, or jog along the

Ride, walk, or jog along the

You have probably noticed a lot of these critters around town lately; they seem to be just about everywhere this time of year. These eye-catching little beasts go by many names, including “Cross Orb-Weaver,” “European Garden Spider,” and “Pumpkin Spider,” among others,1,2 but their proper scientific name is Araneus diadematus. (Note: common names like “Garden Spider” or “Pumpkin Spider” may refer to a number of different spider species, which is understandable given that there are an estimated 47,000 (or more)3 spider species on earth! Since we have not come up with 47,000 unique common names for all of these species, it is best to use scientific names to avoid confusion.)

You have probably noticed a lot of these critters around town lately; they seem to be just about everywhere this time of year. These eye-catching little beasts go by many names, including “Cross Orb-Weaver,” “European Garden Spider,” and “Pumpkin Spider,” among others,1,2 but their proper scientific name is Araneus diadematus. (Note: common names like “Garden Spider” or “Pumpkin Spider” may refer to a number of different spider species, which is understandable given that there are an estimated 47,000 (or more)3 spider species on earth! Since we have not come up with 47,000 unique common names for all of these species, it is best to use scientific names to avoid confusion.) not to hurt large vertebrates like us. And while a bite from one of these guys might be painful and cause a small localized reaction8 (much like a bee sting), the chances of being bitten are so slim that it is a non-issue. These spiders are not the least bit aggressive; they like to keep to their webs and mind their own business, and would only bite as a last resort (i.e. if they were about to be squished). So next time you walk through a huge web that a resident A. diadematus thoughtfully constructed right in front of your door, do not panic – the spider is running for the hills as we speak. If you are lucky, your little 8-legged buddy might stumble into your hands and let you take a closer look!

not to hurt large vertebrates like us. And while a bite from one of these guys might be painful and cause a small localized reaction8 (much like a bee sting), the chances of being bitten are so slim that it is a non-issue. These spiders are not the least bit aggressive; they like to keep to their webs and mind their own business, and would only bite as a last resort (i.e. if they were about to be squished). So next time you walk through a huge web that a resident A. diadematus thoughtfully constructed right in front of your door, do not panic – the spider is running for the hills as we speak. If you are lucky, your little 8-legged buddy might stumble into your hands and let you take a closer look!