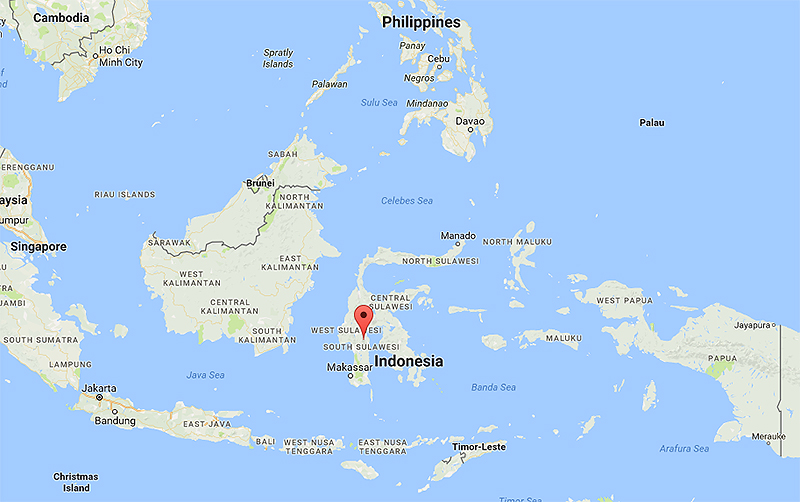

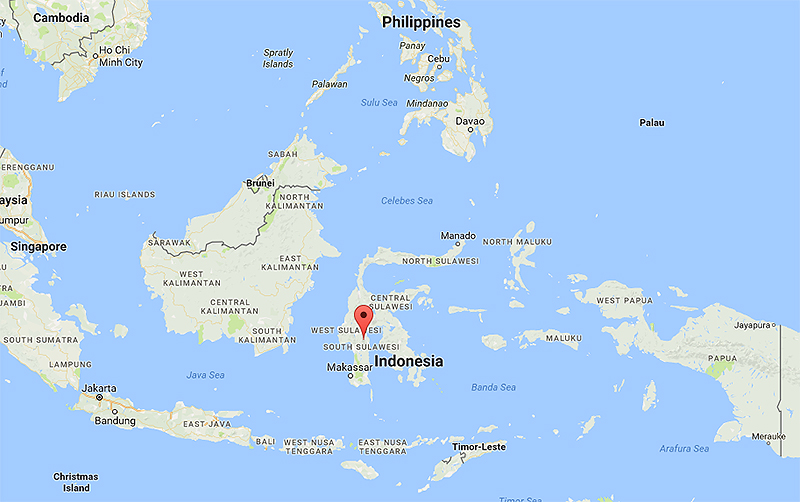

The island of Sulawesi (aka. Celebes) is nestled between Borneo, Papua, and the Philippines in a region of Indonesia known as Wallacea. It was formed by a collision of the Asia plate, Australian plate, and a system of island arcs, each contributing their fauna and flora. The resulting complex biogeographical patterns were a fascination to Alfred Russel Wallace and continue to be for modern biologists. Thanks to an NSF Biodiversity: Discovery & Analysis grant (DEB 1457845) led by Jim McGuire of the Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (MVZ), and co-PIs Rauri Bowie (MVZ), Rosemary Gillespie (Essig), and Susan Perkins (AMNH), a multi-taxon team of biologists will survey an elevation gradient across nine volcanoes distributed throughout the island.

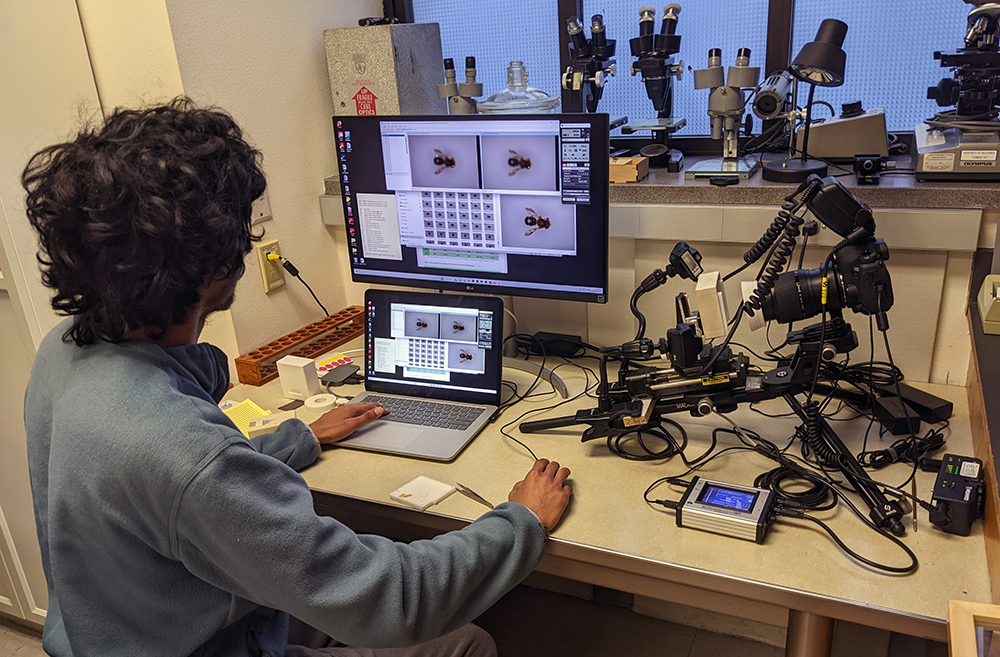

The first expedition in July-August 2016 was to Latimojong in the northern part of South Sulawesi. Six researchers from the Berkeley Natural History Museums: Peter Oboyski (Essig), Jim McGuire, Rauri Bowie, Luke Bloch, Alexander Stubbs, Jeff Frederick (MVZ), along with Heidi Rockney (SF State) met with colleagues from Australia and the Indonesia Research Center for Biology in Bogor, West Java to organize the inaugural trip. Permitting and other paperwork took two weeks onsite, and this was the expedited processing! Fortunately we were able to visit the Museum Zoologicum Bogoriensis and the Bogor Botanical Garden, and buy field supplies while we waited. The entomology collection is extensive with butterflies and other macrolepidoptera, beetles, bugs, bees, and flies well represented. Not so well represented are microlepidoptera and spiders – two of the targets of this expedition. The facilities are modern with good climate control. The well-educated and knowledgeable curators and staff prepare and database accessions, conduct research, and train students. Although there were some language barriers, there were enough people from each team that spoke the others’ language, which greatly facilitated our collaboration.

Two weeks later, over 20 biologists flew from Jakarta (Java) to Makassar (Sulawesi) to purchase final supplies and make the ten hour drive to the town of Belopa where we spent the night. The next morning we made our final push, by 4WD vehicles to the village of Gamaru – our first field camp. The village, at 1350m elevation, included ~20 simple wooden houses within a matrix of coffee plantations, small gardens, ponds, and secondary native forest. Our home for the first few days was the house of one of the village leaders, while a team of local villagers begin building our field camp and porting gear and supplies.

The first week was rainy and muddy, but the new moon was optimal for UV light collecting. On the first night, a sheet hung under the house with a view into the valley below was one of the best nights of moth collecting.

The next camp was at 1730m along a trail leading from Gamaru village. More secondary forest with a lot of invasive plant species along the trail, but native forest off the trail. We set up pitfall traps, malaise tents, and sifted leaf litter to put in winkler funnels at 100m intervals from 1800 to 2400m, but did not acquire many specimens (possibly due to rain or poor timing). Hand collecting for spiders proved very productive. The highest field camp (2800m) was in a dwarf forest / bog along the upper ridge of the mountain – a distinctly different habitat with a unique insect fauna.

The last few days of the three-week field operation was spent in another village at 800m, which was in the process of being cleared for agriculture and development. Remnants of native forest remained and collecting was generally good. But it was clear that this area would soon be completely converted to agriculture, like many rural areas. After returning to Bogor and the museum, it was time to count specimens for export permits and pack our bags.